Air Purifier Sizing: What Do You Need?

Determine The Right Number And Size Of Air Purifier For Your Space

If you’re reading this in order, you’ll note that we’ve already addressed some questions about air purifiers in three previous articles.

- We highlighted the value of getting a proper assessment of your indoor space as a way to answer whether or not you need an air purifier.

- We laid down the key questions and considerations that can help you discern a best-fit solution for your application – noting that not all air purifiers are created equal.

- We cautioned that air purifiers may not always help, especially if deployed poorly. And we started to go into the technical side of things with discussion on air flow patterns and proper deployment considerations.

Tying back to all of these is the question of how many air purifiers might I need? What sizes, types and quantities? In truth, if we take the “assessment” piece further down its natural path, it should help reveal the optimal numbers, sizes and locations of air purifiers you may need (if any!).

Here’s how air purifier sizing should typically be done, for each unique space being considered.

1. Determine first how much ventilation (clean air of a specified quality*) you either need or want as a minimum refreshing into the space every hour or every chosen time period. For example, in terms of how many cubic feet per minute (CRM) or meters cubed per hour (M3/HR) of clean air volume you want exchanged in the space.

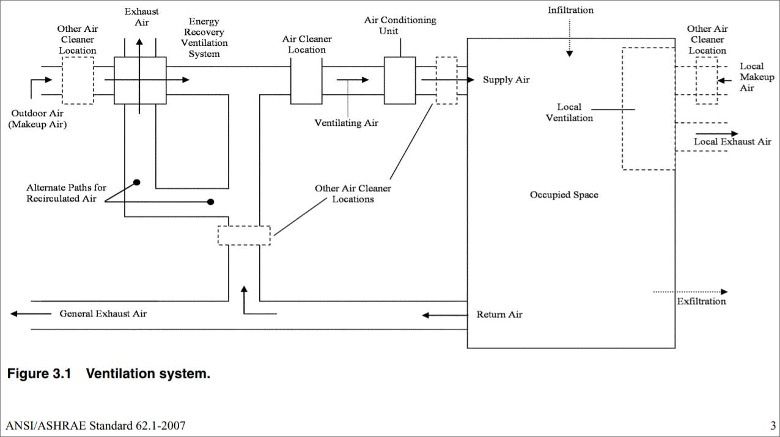

Start with ASHRAE 62.1 as the standard for defining this, for commercial and industrial ventilation applications. CDC and numerous others publish further guidelines to assist in this determination, or to enhance the ASHRAE guidelines for specific targeted applications.

Note that the application and the occupancy of the space make all the difference:

- How many people are accessing the space?

- How much and what types of activity?

- What and how many pollutants are introduced?

- What sensitivities exist?

- How “clean” does the air need to be really?

For example, you would want a lot more (ventilation air flowing in and out of a busy hospital operating room space than into an office supply room that gets used sporadically.

And recent events like COVID may give you reason to increase ventilation rates beyond the ASHRAE standards – you may simply desire cleaner air and better associated risk protection as a matter of personal or corporate priority.

2. Determine your current ventilation flow rates (CFM or M3/HR) into and out of the space (and the quality of air refreshing in).

There are various ways to do this, either calculating the air flows from known HVAC operating balance numbers, or via localized air flow rate measurements using appropriate measuring devices. Understanding whether and how the ventilation changes from time to time is also important.

Note that it may be the minimum ventilation achieved when space is occupied that matters most in sizing an added air purifier(s), rather than an average or maximum number.

3. The difference between these two is how much supplementary clean air (CFM or M3/HR) you need to add into the space or recirculate within the space from your air purifier(s), or from another clean air source otherwise.

NOTE: I’m emphasizing something in the above that you may not see emphasized the same way elsewhere. I believe it’s important to understand and talk about ventilation not just in terms of outside versus inside air alone (which is the common focus), but moreover the quality of the air over and above anything else.

Outside air during wildfire season is not something you would accept or want into a building without filtering and/or conditioning it heavily first. So, I would encourage all of us to think and talk about ventilation in terms of “clean air of a specified quality” entering and exiting the space. Then it becomes obvious that no matter how much air you bring into the space, if that air is below the quality of air you want or need, then you simply can’t count it in the ventilation rates.

As another example, return air that is filtered through a HEPA is clean and can be counted in the ventilation rates. But if the desired quality of air is “COVID-free” and the return air coming back into the space is passing through a substantially-less-than-HEPA filter, then you may not wish to include that return air in the ventilation rates either!

Using Air Changes Per Hour As A Shorthand

While the above three steps may sound doable at first glance, in practice these calculations can get quite complex. The level of detail and inputs needed to come up with valid numbers can be daunting. For example, ASHRAE’s guidelines focus on the air flow rate (cfm’s) needed per person in each type of space. This in itself adds to the complexity of the calculations.

So for the sake of ease and simplification, people often use a much simpler set of guidelines to estimate how much “supplementary” clean air they need or want to add into the space.

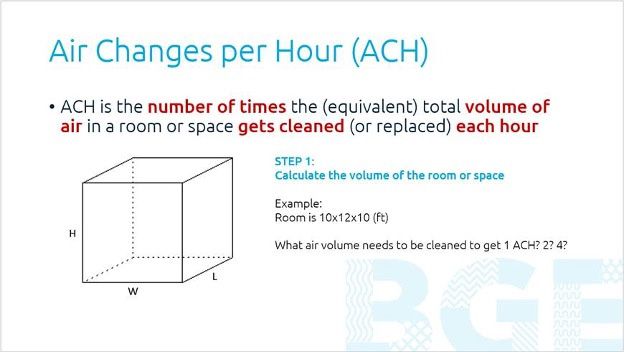

Air changes per hour (ACH) is the number of times the (equivalent) total volume of air in a room or space gets cleaned (or replaced) each hour.

Imagine any room or space you want to imagine. It has a certain volume of “dirty” air in it, let’s say 1200 cubic feet (e.g. 120 square feet with 10 foot ceilings). If over the course of one complete hour you pump 1200 ft3 of “clean” air into the room or space on one side at the same time as you suck 1200 ft3 of “dirty” air out on the other, then you’ve completed one air change of the space over the course of one hour (i.e. one ACH).

If you manage the same feat in just 10 minutes instead of an hour, then you could conceivably complete six full air changes in the space if you kept it up for an hour (i.e. six ACH).

Note that In the second instance, your flow rate of “clean” air into the space is six times as great as the first instance. For a given space and volume, ACH is directly proportional to flowrate of clean air in and dirty air out. In other words, if I need or want more ACH, six times as much as I’m getting right now from my HVAC system say, then I need or want more “clean” air flow into the space, six times as much.

Now consider the application of an air purifier in this same example.

A room air purifier has an inlet and an outlet. It sucks “dirty” air OUT of the room by drawing it into the machine. And pumps “clean” air IN to the room by exhausting it out of the machine. So rather than a separate inlet and exhaust in different locations in a room, it’s combines the two right at the machine and creates both a push of clean air in and draw of dirty air out.

Now if you think on this a bit, you’ll come to realize that you don’t actually ever really replace the entire volume of air in the room in one or even six hours. That’s because the air in the space is always mixing to some extent or other. So there’s simply no wall of “clean” air coming in on the one side that stays completely separated from the “dirty” air leaving on the other as it travels into the room. Instead, the best you can hope for is a high dilution rate.

As you add in “clean” air, you’re exponentially diluting the “dirty” air that itself keeps getting cleaner and cleaner over time. The better the separation between “clean” and “dirty” air flows – inlet and exhaust flow patterns in the space – the better the dilution rate.

There are numerous guidelines out there – including from ASHRAE and CDC – that speak in terms of the number of air changes per hour you might need or want for your space. For example, they might suggest that a typical office space should have between 4-6 ACH (i.e. 4-6 full space volume “refreshes” of the air every hour). This is in fact a common range that BGE might advise for many commercial applications. For critical lab or medical facilities, the recommendation can jump to 12 or even 20 ACH, depending on the particulars.

In most cases, the existing HVAC and ventilation system will satisfy at least a portion of the ACH requirement, if not all, by typically by bringing in relatively “clean” outdoor air and filtering it further to achieve the desired air quality. Return air conditioned and of know good quality can also add flow rates (cfm) to the ACH.

But where more is needed, an air purifier(s) can supplement the HVAC system to achieve the full ACH requirement.

In summary, there are three steps to remember.

- Determine how much ACH you need or want in a space.

- Determine roughly how much ACH the existing HVAC/ventilation system is providing for the space.

- Consider implementing an air purifier to make up the difference. Size the air purifier for the desired ACH addition. The flow rate/CFM is key variable you need to come up with.

And that’s really all there is to it. Provided you have a decent air purifier creating the desired air quality to begin with.

Except for these caveats and considerations.

Sure enough, there are caveats, and a lot of confusing or misleading info that can distract from the task at hand. Let’s look at some of them:

Air purifiers publish flow rate info that may sometimes be misleading or at least inconsistent with expectations.

Does the CFM (or M3/HR) rating apply to the unit with or without filters? If it is rated without filters, then the number is misleading and may be too high to be trusted for ACH calculation purposes. The actual CFM of the unit in operation – with filters installed – may be lower than the vendor is saying it is; and so it may potentially be too weak or inadequate a flow to achieve the ACH you need or want.

We talked previously about air flow patterns. They matter!

An air purifier that is pumping air out and drawing it’s own clean air exhaust back into its inlet because of an inherently poor air flow pattern design or because of interferences in the room is not helping much. It would be achieving a low dilution rate overall for the space relative to a better designed application; and so would not be achieving the desired ACH in practice, even if it may achieve it on paper. ACH and Air flow patterns should always be considered in combination, never alone!

People tend to forget that more air flow (CFM) typically equates to more noise.

So if the air purifier is never operating at it’s rated flow rate because you keep turning it to a lower speed setting to reduce the noise, then it may not be delivering the ACH you need or want in the space, unless that speed setting was the one factored into the calculations in the first place.

Air purifiers are only as good as their quality and materials of construction.

So a HEPA filter that by itself is good may be of little help in generating enough high-quality “clean” air of the kind you were expecting with your ACH calculations if there is bypass around the HEPA in the system. As another example, an air purifier made of poorly chosen materials and with a poor enough design can even add to air quality issues if, say, some components release unwanted volatile organic compounds (VOC’s) into the space (although this can sometimes also be a very temporary “issue” on initial run or power up with even a well-built, well-designed unit).

If you don’t maintain an air purifier – including especially changes filters that are dirty in timely fashion – then it stops delivering the “clean” air that you assumed you’d get in your initial ACH calculations.

You may get sucked into comparing “square footage” ratings without digging deeper, thinking it’s similar but just easier and quicker than ACH comparisons.

You may think you’re getting twice as much CFM from one air purifier versus the next because the one vendor is claiming their unit cleans 500 ft2 whereas the other is claiming theirs cleans only 250 ft2. This can be so very misleading that it warrants this special caution: Just DON’T RELY on square foot data AT ALL! Ignore it completely. Instead, think about:

- What is the ACH basis? If one vendor is using 2 ACH as their basis for their square footage rating and the other is using 1 or 4 ACH as their basis, and both claim the exact same square footage rating, then one could be half or twice the size of the other in terms of real airflow (CFM).

- What is the volume of the space, because that is really the only room dimension that matters, not square footage! If one vendor is assuming an 8 ft ceiling and the next a 16 ft ceiling, then even if they are both advising the same square footage rating, one is again delivering twice the real airflow (CFM) versus the other. Because one space is twice the volume versus the other with the same square footage.

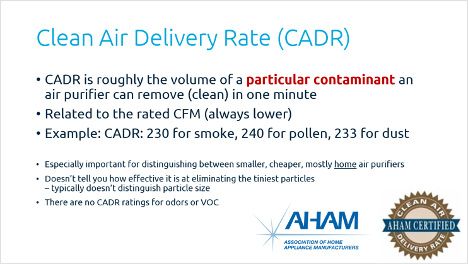

Likewise, you may feel the urge to give undue weighting to the CADR ratings of one unit versus another, perhaps even thinking this is a true measure of the unit’s airflow (CFM).

CADR stands for “Clean Air Delivery Rate”. It is a standard created for home air purifiers and serves a purpose in helping the average consumer make relative decisions with a simple, clear numeric rating. But that doesn’t mean that CADR is the comparison parameter you want to rely on for your commercial or industrial or even personal application.

This is because CADR provides only a very rough indication of how an air purifier performs for a very specific, narrow range of contaminants – dust of a particular size, smoke of a particular size and pollen of a particular size. A specific home air purifier typically will have a rating for all three of these separately.

At best CADR ratings give a relative comparison that you can use to very roughly gage the unit’s effective airflow (which is always less than its max rated airflow) and get a feel for how the unit performs for a very narrowly-defined band of contaminants. But these may not be the contaminants or size of particles that you do or should care about for your application.

All of which makes CADR too vague and meaningless a parameter for most commercial applications.

As one example of this, two air purifiers could have the exact same CADR rating, but one effectively removes 99.9% of COVID virus particles and the other less than 50%. There are no CADR ratings for viruses and microbes at present.

Your Partners In Clean Air

Call 780-436-6960 today to speak with a BGE Clean Air Advisor.